By Erik Skindrud, InfoWise.org

An early-1960s vision for San Gorgonio Ski Lifts, Inc. strung a gondola from 9,000 ft. to 11,450 ft. near the peak’s summit. Photo is screen grab from YouTube post “Skiing Jepson & Charlton Peaks.” Video showcases near-perfect conditions on Feb. 26, 2022. Gondola image is Eiger Express in Grindelwald, Switzerland. (Main photo: Preston Lear/SierraDescents. Eiger photo: Drew Gorski. Photo illustration: Erik Skindrud.)

Summit fever gripped Southern California skiers 60 years ago this autumn — as plans for a multi-chair ski area (with one gondola) seemed poised for breakthrough onto Mt. San Gorgonio’s upper slopes.

Warren Miller played a role. The filmmaker had launched his ski career at Mt. Waterman above Los Angeles — and was a leading donor to the San Gorgonio effort — listed in an October 1963 fundraising statement.

Joining Miller was Alex Deutsch, a factory owner who pledged $160,000 to train skiers for the 1972 Olympic Games. The scheme had one stipulation — that San Gorgonio’s upper slopes open for development.

“The very nature of the mountain is a perfect… for the training of ski racers,” Deutsch argued in a March 8, 1964 New York Times article. (The piece includes responses from the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society.)

The real animal behind the push hailed from Pasadena, however. Howard More was an evangelist of skiing who had run Wrightwood’s Ski Sunrise area since 1943. If anyone, More had the right stuff to dream the impossible — and then build it.

“The man was a force of nature,” Bob Roberts, executive director of the California Ski Industry Assn., said after More’s passing in 2006. “He also took stubborn to a real high. And that’s what it took in the early days to get going.”

John Elvrum, the Norwegian ski jumper who spent decades developing Snow Valley, was also on the team.

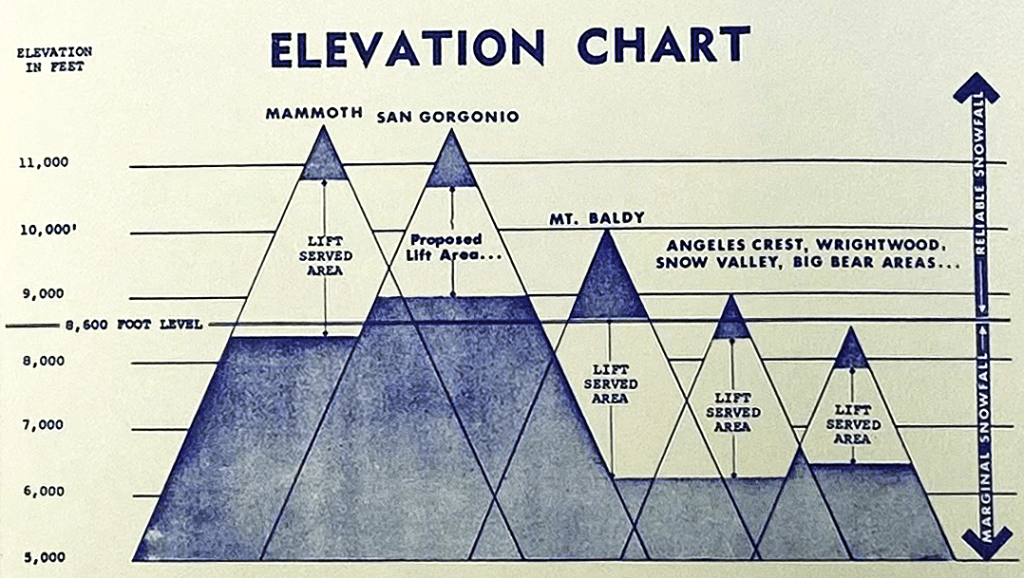

These believers shared a vision — of a sort of So Cal Mammoth Mountain. That’s how it was pitched to the public — a high-elevation resort with reliable snow and expansive lift system. And not only for elites, but for families from across the L.A. Basin — requiring less money for gas and overnight lodging.

San Gorgonio Ski Timeline

| 1931 | First ski ascent of 11,503-ft. Mt. San Gorgonio on Feb. 3 by Murray Kirkwood and three Pomona College students. |

| Early 1940s | “Present conditions… are deplorable. One slope of the mountain has been almost denuded… to make way for a ski run. Half a dozen to a dozen shacks and shanties have been constructed… as overnight shelters for skiers… (with) no provisions for toilets.” –Harry James. |

| 1947 | Chief Forester Lyle Watts renders a decision barring ski development on the mountain. |

| 1964 | Congressional hearings on ski area plans — followed by decision to delete 3,500 acres from the San Gorgonio Wild Area to pave way for ski development. Then, on Sept. 4, President Lyndon Johnson signs the 1964 Wilderness Act, quashing development plans and establishing the San Gorgonio Wilderness. |

| 1965 | So-called Dyal Bill, written to remove swathe of San Gorgonio Wilderness for ski development, fails to advance in House of Representatives. Two years later, a similar bill stalls. |

Recalling the battle is of interest for an obvious reason. Studies see snow levels rising over the next half century. This is especially true in Southern California, where resorts based around 7,000 ft. are unlikely to be in business 50 years from now.

By the 2080s, 11 of 21 former Winter Olympic sites are projected to be too warm to host another Games — among them are the former Squaw Valley, California, Vancouver, British Columbia, and Chamonix, France.

Musing this led me, in April, to Norco, California (Riverside County) — home of the California Ski Library. The facility is run by Ingrid P. Wicken, who likely knows more about the history of Golden State skiing than anyone. (She’s author of “Pray for Snow: The History of Skiing in Southern California” (2001), “Lost Ski Areas of Southern California” (2012), and other works.)

That morning, the lift operator at Mt. Baldy’s base yawned when he saw my tele bindings. The snow’s spring consistency would take a toll, he knew. “You gonna get a workout on that gear today,” he said.

Weeks earlier, Wicken emailed that she had something to show me. The library possessed renderings showing proposed chairs and runs for the area.

She had more. Her file on San Gorgonio holds a trove of letters, photos and press clippings — many from longtime Ski Sunrise owner Howard More. The Pasadena resident had spent decades struggling to make the Wrightwood location work — today it is a climate-change casualty.

In 2003, Wicken visited More in Pasadena. The dream was still etched in his head.

“He was still adamant that it should be done,” Wicken recalled earlier this year. “He said, ‘You and I could do it!‘”

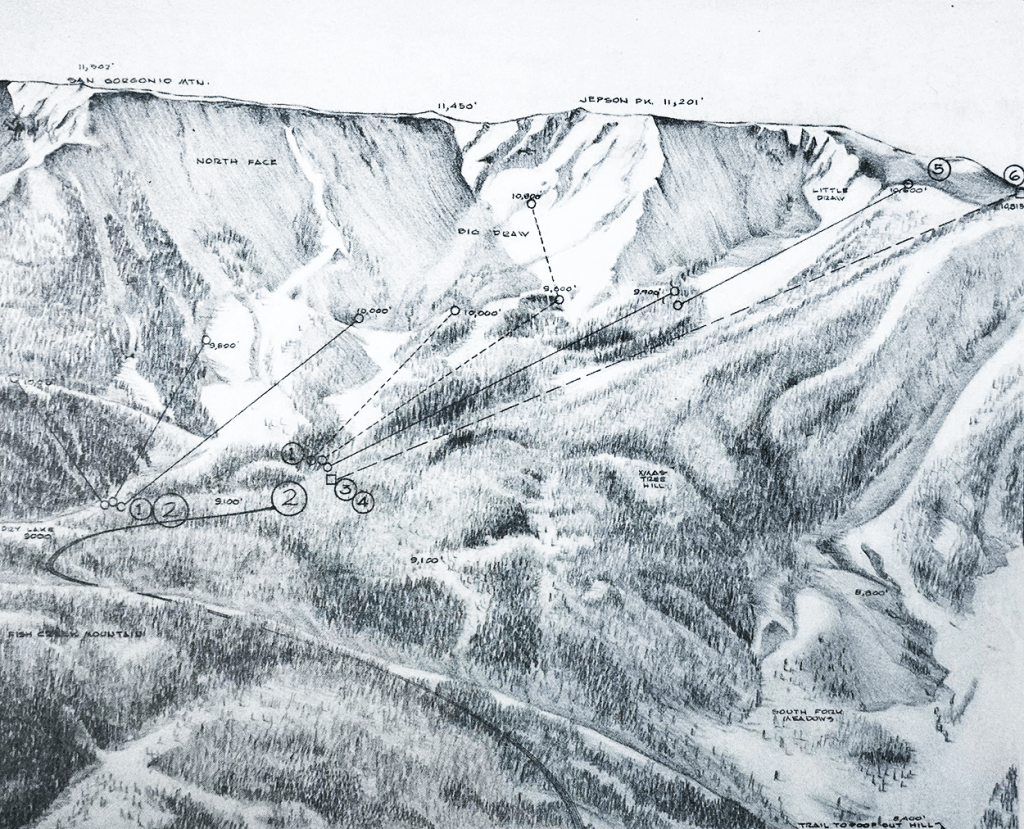

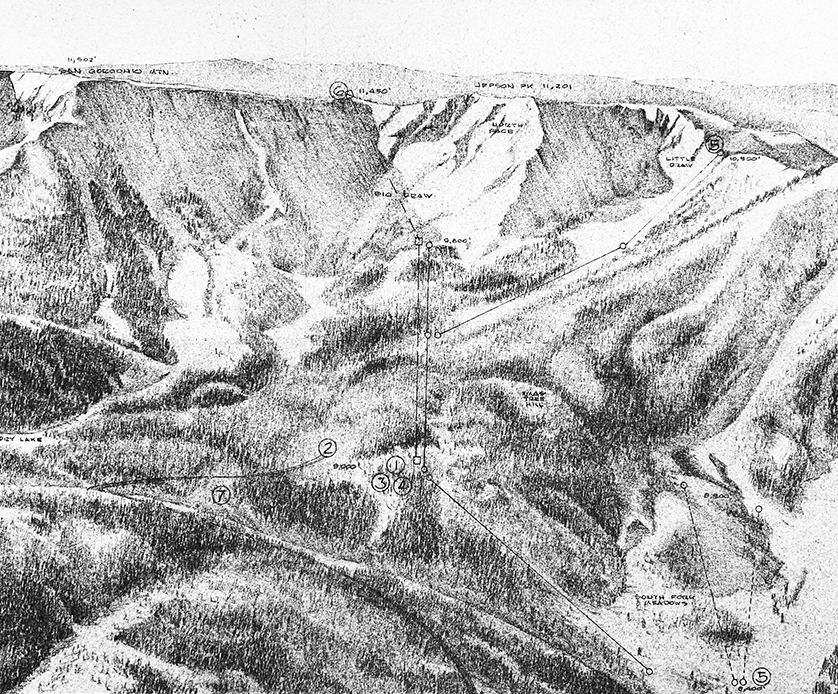

At Norco, Wicken unveiled the renderings. The older, from 1962 perhaps, showed the parking lot and base area west of Dry Lake at 9,000 ft. From that point a chair lift paralleled a gondola up to 9,600 ft. From there, the gondola went to the top of the Draw at 11,450 ft. That’s higher than Mammoth Mountain’s summit (11,053 ft.).

West of the Draw, more chairs served 10,900 ft. on Charlton Peak. The system accessed an array of chutes and bowls. The vision remains seductive — even 59 years after the 1964 Wilderness Act.

What if we could press a magic button and make the resort materialize, I asked Wicken. Would you do it?

“It was the right decision (not to build it),” she said.

With comments or corrections, please email eskindrud@gmail.com.