By Erik Skindrud, InfoWise.org

More than a hundred years ago, movie star Florence Lawrence moved to Los Angeles, where she would reside until her death shortly before World War II.

Today almost completely unknown, Lawrence’s story spotlights strands of history that make Southern California – and America – what they are today. Her tale also underscores some sadder trends that continue to dog Californians and the country.

The holidays are an appropriate time to tell Lawrence’s story. She was born on Jan. 2, 1886 – and died, by her own hand, on Dec. 28, 1938.

“Men amuse me, really. They are so bombastic.”

–Florence Lawrence, 1920 newspaper interview

Lawrence stepped off the train from San Francisco seeking a comeback in a Hollywood she had helped invent – without ever working there. She was 34 years old. It was a decade after her glory years as the first American movie star – a distinction most film historians agree she holds.

D.W. Griffith, her principal director, made films in Southern California in 1910 and, of course 1914, when “The Birth of a Nation” riled racial tensions. Lawrence worked under Griffith in New York and Connecticut. (Griffith fired Lawrence several years earlier, in 1909, when she went to work for Carl Laemmle, cofounder of Universal.)

[Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research]

“This is my first visit to Los Angeles, as I was never sent west to make pictures,” Lawrence told the Los Angeles Evening Express after arriving on Dec. 16, 1920.

But the Lawrence who stepped off the train was more than a fading idol. She was president of the Bridgwood Manufacturing company of New York, the first American to design a working automobile turn signal. The firm also offered a first-generation windshield wiper.

Turn signals, of course, are in declining use today. Their fading utility marks the sort of difficult-to-measure cultural evidence Robert D. Putnam cites in “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.” The Harvard political scientist’s 2000 work examined the decline of American “social capital,” which continues to bedevil our politics, public health and daily life.

Data on turn signal use is hard to come by, but a 2012 survey by the Society of Automotive Engineers found close to half of drivers admitted to not signaling when changing lanes. Amusingly perhaps, a portion said ignoring their signals “adds excitement to driving.”

It’s also likely that many view turn signals like face masks – a requirement to be tossed away in the name of personal freedom. Dangerous driving has grown by leaps and bounds in the covid pandemic’s wake. Astonishingly, close to 43,000 Americans died in vehicle accidents in 2021 — a 16-year high following years of safety improvement — the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reports.

It’s hard to compare drivers and automobiles a hundred years ago to the present day. But Lawrence certainly combined a measure of thought and consideration for both.

“A car to me is something that is almost human, something that responds to kindness and understanding and care, just as people do,” she said in a 1920 interview shortly before her move to L.A.

Others would devise and profit from their own wipers, brake lights and signals. Lawrence, however, retains credit for the turn signal – in a 2013 New York Times item, with the Lemelson-MIT Program for engineering education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and with the Pennsylvania-based Historic Vehicle Association, among many others.

It likely didn’t help Lawrence that she lived in a more male-dominated world than our own. Even if the country had just certified the 19th Amendment guaranteeing a woman’s right to vote – the same day as the interview, by chance.

“Above all, (Lawrence) is an ardent suffragist and defender of women’s rights,” the interview notes. The actor could not resist a nudge at males in general.

“Men amuse me, really,” she told the reporter. “They are so bombastic.”

Lawrence’s story ends badly, a preview of Hollywood biographies to follow.

“By 1921 the art and business of film had changed beyond her recognition,” culture scholar Ethan Mordden noted in 1983.

For the record, Lawrence wielded significant talent. Raised on the stage, she was master of pantomime ranging from vulnerability to moxie. A delicious hint of her presence exists in 1931’s “The Hard Hombre,” one of her few speaking roles preserved today.

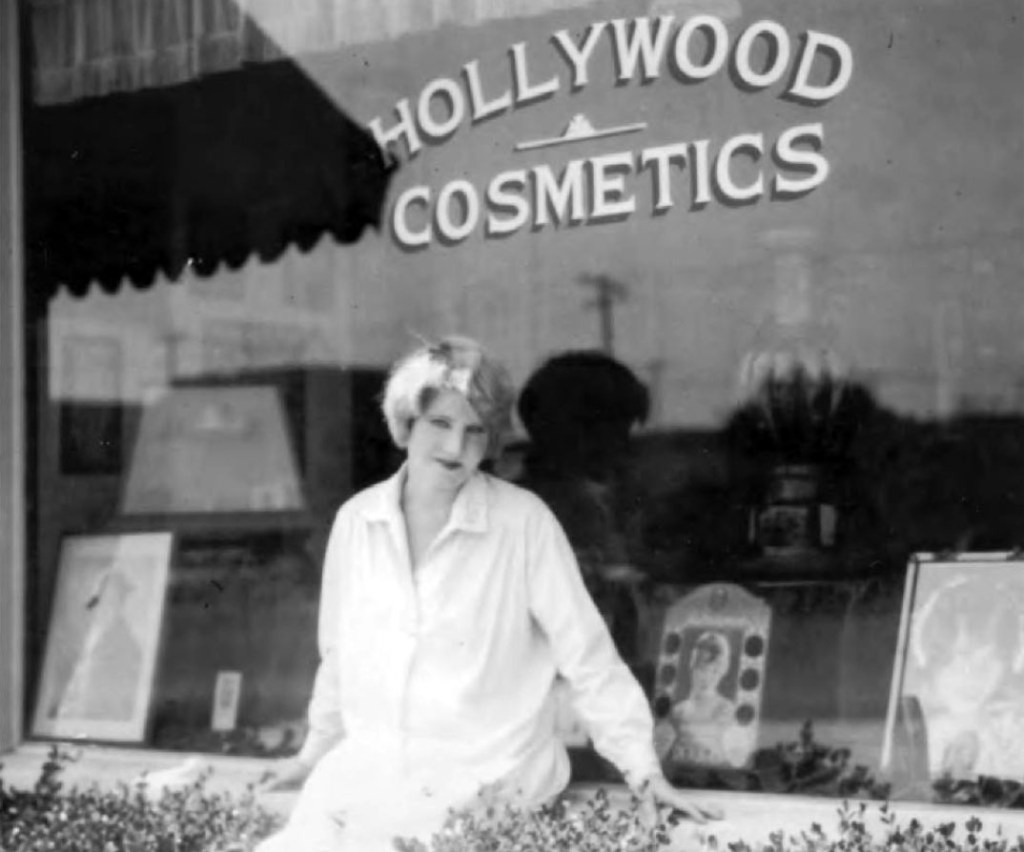

Photo courtesy of Kelly R. Brown, author “Florence Lawrence, The Biograph Girl: America’s First Movie Star (2007).

The same year saw the end of her last business – Hollywood Cosmetics, on Fairfax Avenue. She persevered until 1938, when depression and failing health led her to consume a cocktail of cough syrup and ant poison. She was 52.

“I am tired,” she wrote in a note. “Hope this works.”

She remains a historical footnote – although a vivid one for cinephiles. Mexican filmmaker-scholar Carlos Bustamonte offers the following appreciation.

“Florence Lawrence’s acting, her ability to develop several emotional levels seemingly simultaneously, thrills me more than watching a well-edited chase,” the Berlin-based academic told biographer Kelly R. Brown. “Her timing, the quick-changing expressive control of her body, head and hand movements, the alternating degrees of tension and relaxation, gracefulness and woodenness are a joy to watch and follow.”

A number of Lawrence’s performances, as early as 1908, are viewable on YouTube.

Lawrence today rests in Hollywood Forever Cemetery just off Santa Monica Blvd., about four miles from Westbourne Drive – where she died in a portion of Los Angeles that today is West Hollywood.

The year following her death, in 1939, the Buick Motor Company began installing turn signals as standard equipment.

Erik Skindrud is a writer based in Long Beach, Calif.